There were many different things that unions demanded during the Gilded Age, with higher wages and fairer working conditions topping the list.

The Gilded Age in the United States ran from the 1870s to the early 1900s. The term “The Gilded Age” stemmed from the 1873 novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, written by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, which chronicled life in the United States after the economic boom.

The unions during the Gilded Age in the United States demanded better working conditions and higher wages.

These unions were ones that fought to the literal death in some cases in their attempts to have these demands met.

Union action during this time was among the most contentious and bloodiest in American history, with federal intervention often required.

Table of Contents

What was the Gilded Age?

The Gilded Age was a term coined by authors Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner to describe a time in American history when the economy was booming.

The global economy matched this time, with the Victorian era in Great Britain and the Belle Epoque era in France occurring simultaneously.

The American term, the Gilded Age, referred to an era where economic growth was marked by gilded homes and glittery lifestyles.

However, underneath the glitter and glamor was a frequently disgruntled working class. The wages grew for everyone during the Gilded Age, but industrialization was increasing the level of competition for both big businesses and the working man and woman.

At the same time, the country was being flooded by immigrants, and labor competition was fierce.

Wages nearly doubled during this time, with the average American annual wage growing from $380 to $564.

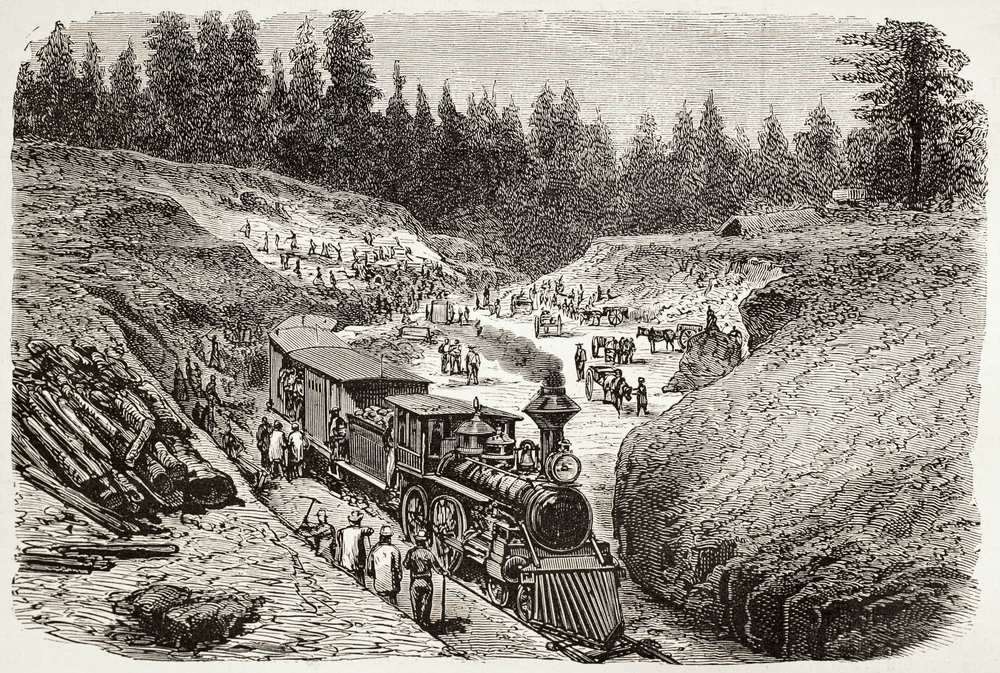

Still, as the railroads grew – a key bone of contention in the labor forces – poverty and inequality prevailed in the working class.

At least three major labor strikes occurred during the Gilded Age as a result.

What was the Great Strike of 1877?

The Great Strike of 1877 was the first of many devastating blows to the working class during the Gilded Age.

This was one decade after the Civil War and a few years after the depression that began in 1873.

Railroad companies felt forced to begin reducing the pay of their workers, who had already experienced 10 percent wage cuts.

An additional 10 percent was cut in 1877, and this made life unbearable for railroad workers already struggling to survive.

Some would be sent away to work and be forced to pay for their own accommodation, further decreasing their living wage.

To make matters worse, jobs were also cut, increasing the workloads of the existing labor forces.

The Great Strike began on July 16 in West Virginia, spreading to Baltimore, New York, St. Louis, Chicago, and arriving in Pittsburgh by July 19.

The state militia was called into Pittsburgh, an exercise in futility for railroad owners as they sympathized with the railroad workers.

By July 21, more troops arrived with arrest warrants for the leaders of the strike action, a move that resulted in a bloody open fire leaving 20 dead and 29 wounded.

Did military action end the Great Strike of 1877?

No, this action that resulted in at least one woman and three children dead did not end the strike. Strikes end after labor negotiations and this was not enough.

Still, defensive action was required to intervene with this bloody mess.

By July 26, President Hayes ordered in the federal troops from the United States Army and the railroads began to open again.

By the end of July, the railroad was returned to its original working state, with nothing but a few horrifying memories to show for it.

It would be the first time in American history that the federal government was called in to cease a strike action against wage cuts.

This strike was, to many, including the President of the United States and the news media, referred to as an insurrection.

The weaker parties here were the railroad owners, who served up a human cost to capitalism. At the time, thousands of workers felt oppressed, and the strike was considered a new revolution of its own kind.

Were there more strikes during the Gilded Age?

Yes, labor strikes during the Gilded Age continued. The union of the Knights of Labor thought of initiating a labor action in 1884 against the Wabash Railroad.

The entire workforce was paralyzed by 1886, but the union would have over 700,000 workers in it by the end of the year.

By 1886, Knights of Labor began a strike that would encompass several states, including Missouri, Texas, Kansas, and Arkansas.

Again, better wages and improved working conditions were the prevailing complaints. This strike became violent.

IT began on March 7 when a Knights of Labor member was fired in Texas for having a company meeting.

The meeting involved getting on a train and intentionally killing its mechanical engine. By March 20, the railroad bridges in Texas would be burning, which resulted in some resolutions whereby many leaders thought the strike was over.

Was the strike in 1886 over in March?

No, the strike was not over here. Hiring discussions launched after this action suggested that those involved in strike action, in thought or deed, could not be hired.

This resulted in more violence in the south.

At this time, the south was already stressed economically. Without industry, the south relied on cotton and tobacco farming in an economy where prices were falling.

Industrial work was a necessity to survive.

With workers being discriminated against, violence and protests erupted – in some cases, between the workers and police action initiated to stop the violence.

The Knights of Labor encouraged its members to continue striking. This strike ended in May of 1886 when a special Congressional meeting intervened to end the labor dispute in favor of the railroads.

Did this end railroad strikes for good in the Gilded Age?

The Gilded Age was a colloquial term used by authors to describe the vanity of life behind glass doors for people that were oblivious and apathetic to the toils of the working man and woman.

A congressional intervention ended one strike, but it did not end the plight of the labor force.

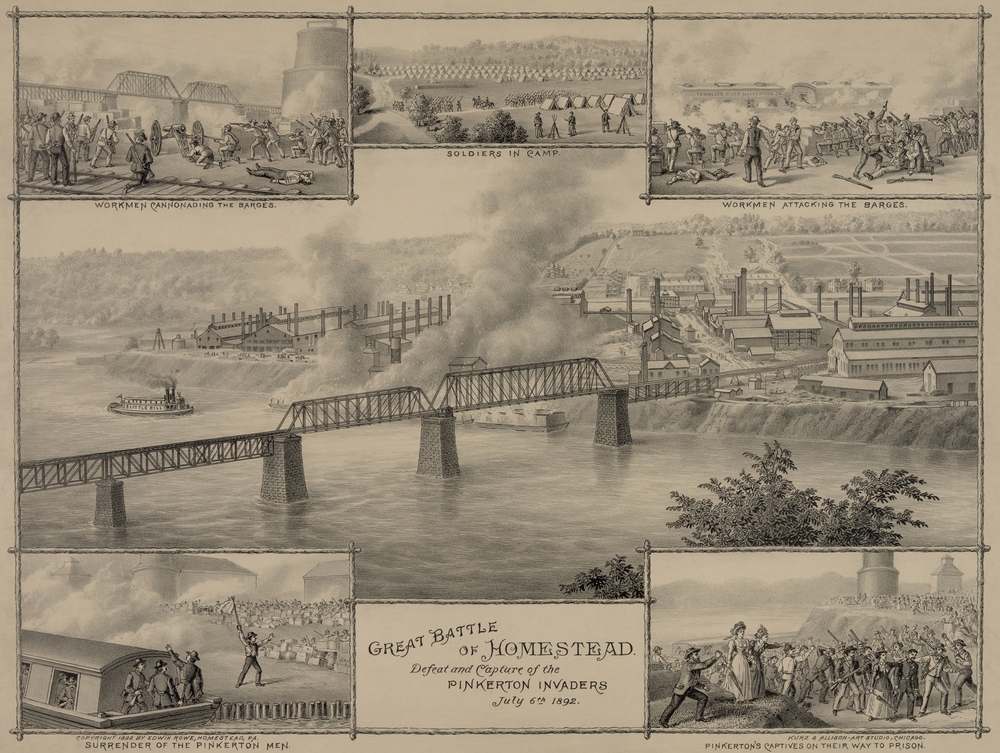

By 1892, the infamous Homestead strike of the Homestead Steel Works plant, again near Pittsburgh, erupted amongst steelworkers.

This was another strike that got bloody, and the owners saw it coming. Andrew Carnegie had placed Henry Frick as the head of his operation here, hoping that Frick would implement a policy that would abolish the union class.

Still, Carnegie had some vision and was in favor of unions personally and publicly, just not for his own business.

He ensured the workers would produce enough inventory to have on hand in the event of a strike.

Come June 30, 1892, the collective bargaining agreement was set to expire, and the negotiations began, resulting in the Homestead Strike.

What did the workers in the Homestead Strike want?

The workers in the Homestead Strike were fighting for higher wages. Frick was leading in the other direction, seeking a 22 percent wage decrease that impacted over half of the union at the time.

Higher positions were also on the chopping block.

Even Carnegie did not like the proposed changes, considering them elitist and discriminatory, and even anti-American.

By April 30 of 1892, Frick announced that negotiations would continue for another month, and if they failed, the union would be dissolved.

It was a move formally approved by Carnegie, as it came with a slight wage increase.

The plan didn’t work, with a worker’s lockout occurring on June 28, and no bargaining agreement in place.

The lockout included barbed wire, sniper towers, and water cannons. By July 6, blood had been shed and the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers had been defeated.

Were there any more strikes in the Gilded Age?

The Gilded Age was about clear lines being drawn between the working class and the people they reported to.

There were more strikes over wage issues. Another notorious strike occurred between Pullman Palace Car Co. and its workers.

At the time, the owner of the company, George Pullman, was viewed as a benevolent and generous man, but his workers did not think so.

He was seeking a wage cut by 33 percent, resulting in what would be referred to as the Panic of 1893.

When the wage cut was proposed, housing cost cuts were not, and the workers were not okay with that.

Again, strike organizers were fired, and a strike ensued. This strike was as bloody, with President Cleveland ordering 10,000 federal troops to stop the strike.

It was another strike where the union, in this case, the American Railway Union, was defeated.

Do you want to learn more about the Gilded Age?

The Gilded Age in America was a fun time for some and a bloody time for others. It was also a time of post-depression recovery, where good work was hard to find and yet a matter of survival.

When work was found, Americans fought for their rights to keep it and to keep putting food on the table.

In this era, the unions were always fighting for a better life. They always wanted to make more money for their families and their homes.

They were willing to die for it but ultimately preferred to see peaceful negotiations result in better wages and fairer working conditions.

In the end, the greatest strikes that occurred during the Gilded Age did not meet their goals and resulted in bloodshed and fatalities.

Learn more about the Gilded Age and the plight of the American worker through these stories.