When World War I first began in 1914, Americans had no problem staying neutral. Public support for either side of the conflict was pretty much split down the middle.

As a nation of immigrants, half the U.S. population rooted for Great Britain, France, and Russia, and the rest supported Germany and Austria-Hungary.

In the beginning, the outbreak of war was also good for business. American shipments of manufactured goods and food supplies for sale to the belligerent powers helped to bring the country out of a recession.

There was also broad support for isolation and neutrality. President Woodrow Wilson won reelection in 1915 with the slogan “He kept us out of war.”

Had Germany avoided some colossal blunders, the U.S. could have stayed neutral while Europe’s armies bogged down in the stalemate of trench warfare, and either or both sides sued for peace.

Eventually, as the war spun out of control, it became impossible for the U.S. to maintain its neutrality.

Events that forced the United States out of its isolation and neutrality in World War I included:

- The resumption of unrestricted German submarine attacks on commercial shipping

- The infamous Zimmerman Telegram

- The overthrow of the Russian monarchy

- Historic relationships with Great Britain and France

- Protecting U.S. financial interests

- President Wilson’s hopes for a “war to end wars” and the League of Nations

Table of Contents

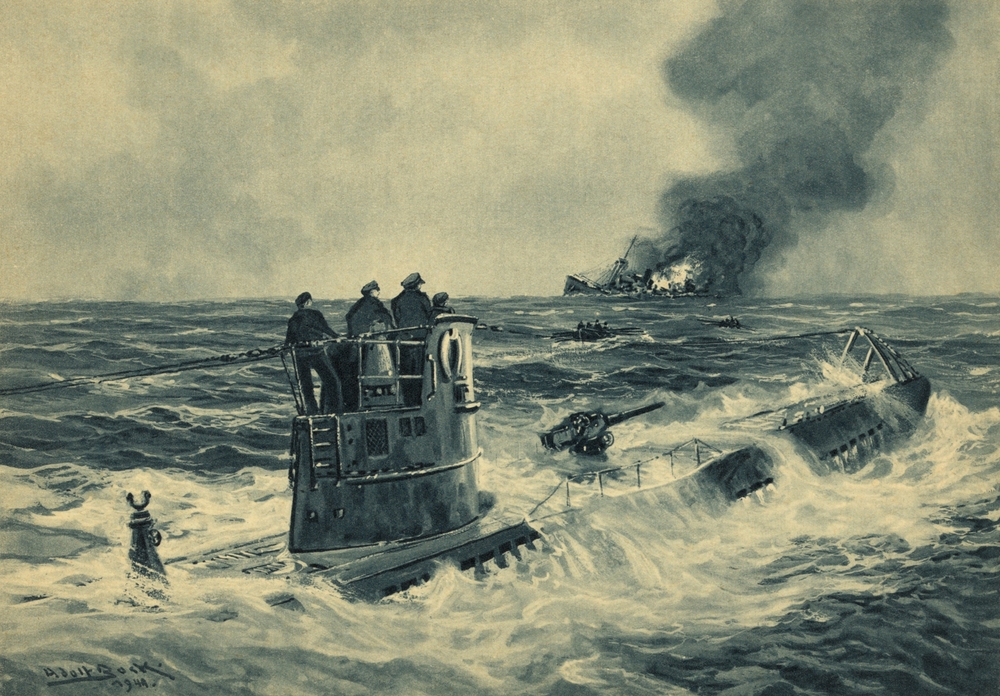

Germany’s Submarine Campaign

At the beginning of the war, Germany declared the sea area surrounding the British Isles a war zone.

Merchant ships, including those from neutral countries like the U.S., were considered fair game.

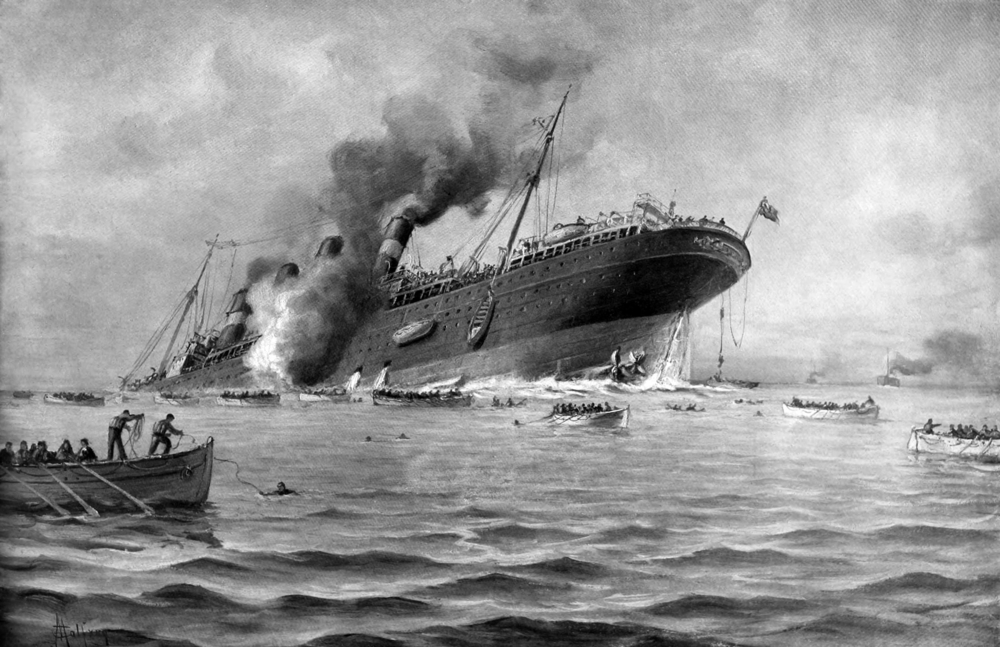

Attacks on merchant ships were followed by the sinking of the British passenger ship Lusitania in May 1915.

Over 1,200 people drowned, and casualties included over 100 American nationals.

(Later, the German government correctly pointed out that the Lusitania was carrying a hefty amount of war materials in its hold and was a legal target.)

An angry message from President Wilson to the German government demanded an end to German attacks against unarmed merchant ships.

Bowing to international pressure, the German government imposed heavy restrictions on submarine tactics.

So, in the early stages of the war, the German Navy suspended U-boat warfare altogether. When the Germans realized they could not defeat the British surface fleet, they had no choice but to resume unrestricted submarine warfare.

In 1917, German navy commanders convinced Kaiser Wilhelm to resume its widespread U-boat attacks.

Against the advice of the chancellor, and faced with a crippling British blockade, the Germans announced that unrestricted submarine warfare would resume on February 1.

In President Wilson’s view, an attack on world commerce was an attack on everyone. It was another nail in the coffin of American neutrality.

The Zimmermann Telegram

After the Kaiser decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, his foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a telegram to an ambassador in Mexico City.

The famous Zimmermann Telegram turned out to be one of the major causes of American entry into World War I.

The telegram proposed an alliance between Mexico and Germany. If the U.S. entered the war against Germany, the telegram proposed, Germany would provide financial and material support to Mexico to recover Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

Those states were absorbed by the U.S. after the war between Mexico and the United States in 1836.

Unfortunately for Germany, British intelligence intercepted and decoded the telegram. The British leaked the contents to the American news media, and the revelation enraged American public opinion.

The German cause wasn’t helped by the German Foreign Secretary. Zimmermann didn’t bother to deny the plan and publicly admitted on March 3 that it was genuine.

Mexico, in the midst of its own civil war, decided to pass on the offer. Besides, the United States was far stronger militarily, and Mexican leaders could not foresee any scenario where they could win, much less hold onto those lost territories.

The Overthrow of the Russian Czar

While unrestricted submarine warfare and the Zimmermann Telegram were important factors changing American neutrality, the March 1917 Russian Revolution also played a part.

The March 1917 Russian Revolution ended czarist control of Russia. The democratic revolution against czarist despotism was an ideal opportunity to illustrate how the war against imperial Germany could be a way to advance democratic principles in Europe.

A provisional Russian democratic government lasted only until October when the Communists took over.

But before the rise of Lenin and the Soviet Union, the United States was the first to recognize the new democratic government.

Along with Great Britain and France, the allied powers were desperate to keep Russia in the war against Germany.

Unfortunately for the allied cause, when the Bolsheviks took power, Russia withdrew from the war, easing the pressure against the German war effort.

Many believed that with Russia out of the war, America should step in and restore the military balance.

Also, the Communists, who were anti-religion and against private ownership of property, served as another object lesson on the value of maintaining democratic institutions.

Historic Relationships with Great Britain and France

Despite turbulent beginnings – the American revolution in 1776 and the War of 1812 – the United States had a history of strong business and cultural ties with Great Britain.

So, there was a natural inclination to support America’s “British cousins” in their struggle against their royal family’s own cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm.

Many remembered Great Britain’s own neutrality during the American Civil War 50 years earlier.

Had Britain supported the Confederacy, it could have prolonged the war between North and South and possibly resulted in a breakup of the U.S.

Likewise, Americans remembered France’s help during the American Revolution. Speaking on behalf of General Pershing, the leader of the American Expeditionary Force, Colonel Charles Stanton, addressing a French audience, said, “The fact cannot be forgotten that your nation was our friend when America was struggling for existence…”

Colonel Stanton capped off his address with the famous greeting to the long-dead French hero of the American Revolution, “Lafayette, we are here!”

Also, the iconic Statue of Liberty that was Frances’s gift of friendship to the United States and had been dedicated just 28 years before the war began.

Protecting U.S. Financial Interests

At first, everyone expected that the U.S. could deal equally with both sides of the conflict. Those hopes were dashed as Great Britain bottled up Germany with an effective embargo.

The British received complaints from American diplomats when British obstruction turned back American goods.

But British leaders were not sympathetic.

In the end, circumstances forced American businesses to focus on the British war effort.

Finally, before the war, the United States was a country in debt to other nations. When war came, the United States emerged as the world’s largest wartime creditor, lending over $5 billion to Britain and France.

President Wilson’s Idealism

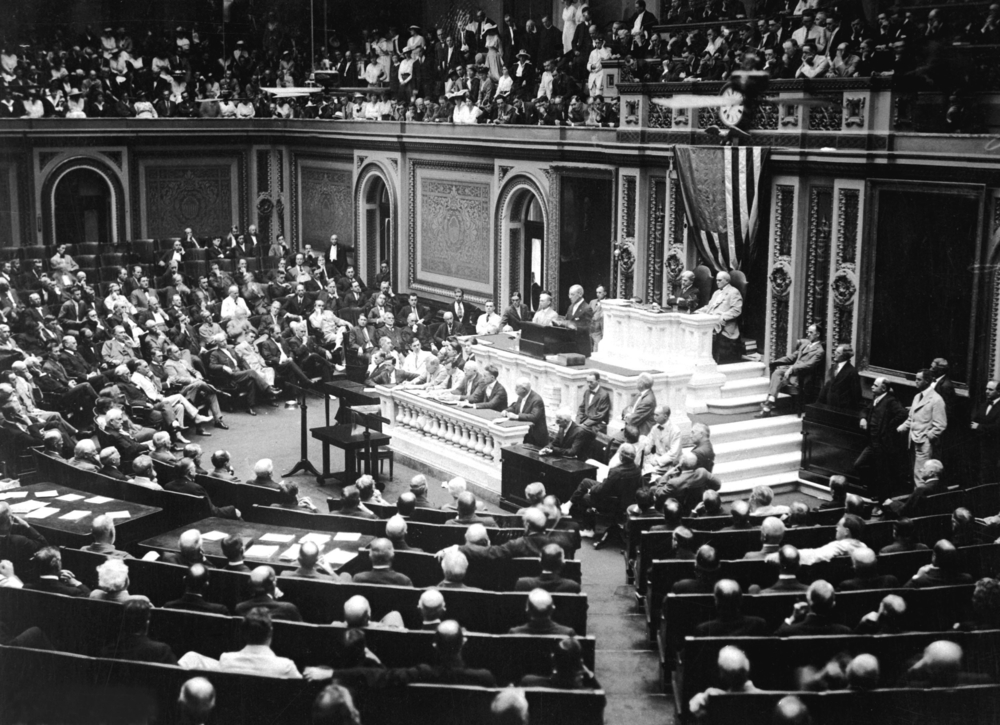

As war fever swept the nation, the U.S. Congress felt the heat. President Wilson’s cabinet unanimously recommended asking Congress for a declaration of war against Germany.

On February 8, 1917, Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress. Buoyed by public opinion and outrage over the Zimmermann Telegram, Wilson asked Congress to declare war.

Congress obliged four days later, declared war on Germany, and signed the Selective Service Act of May 1917, requiring men between 21 and 35 years of age to register for the draft.

The United States would eventually deploy four million troops that would turn the tide of battle and help win the war for the allies.

President Wilson was an idealist. He wanted to, as he put it, “make the world safe for democracy.”

The current war, he claimed, was a “war to end all wars.”

The irony that war actually promoted more violence wasn’t lost on Wilson.

Shocked by the cheers and enthusiastic public acceptance of ending American neutrality and sending young men to war, Wilson broke into tears when he told his advisors, “My message today was a message of death for our young men. How strange it seems to applaud that.”

The President was correct. American casualties amounted to over 250,000 dead and wounded. When the shooting stopped, instead of looking for ways to save future generations from the slaughter of war, the allied victors imposed vindictive and crippling war reparations that laid the foundation for World War II.

Wilson’s Fourteen Points

So, Wilson ended U.S. neutrality in World War I, hoping to play a major role in preventing future wars through negotiation and international cooperation.

He incorporated that idealism into his Fourteen Points.

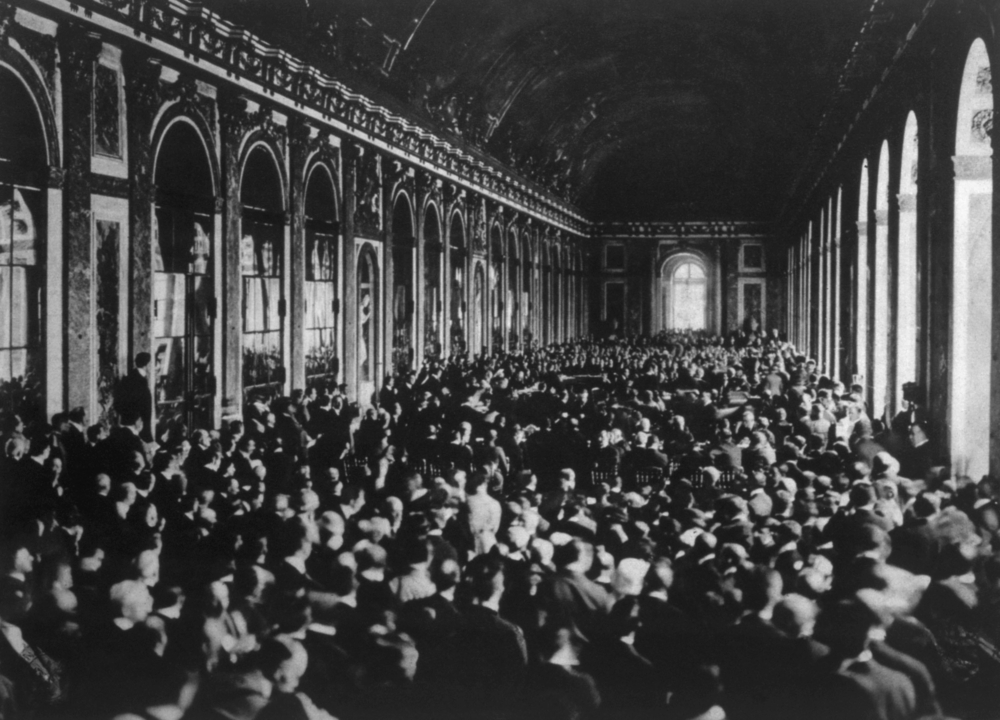

Wilson arrived at Versailles after the war with his idealistic peace plan, but France and England were in no mood for idealism.

France had, after all, lost millions of men and suffered mass destruction at the hands of the German “Hun.”

Great Britain regarded the American President as a naïve idealist and relegated Wilson to the sidelines.

The League of Nations was a Package Deal

Wilson, then, had to settle for “half a loaf” and hoped to salvage the imperfect peace. He wanted American membership in the new League of Nations.

He could only get that through Senate ratification of the terrible Treaty of Versailles.

Wilson truly believed in the concept of world government where national sovereignty took a back seat to the wishes of a world governing body, i.e., the League of Nations.

But American isolation wasn’t dead yet. The new Senate Republican majority and a few Democrats voted against the treaty and scuttled Wilson’s plans.

The Treaty was defeated in the U.S. Senate by seven votes. Ironically, Wilson instructed members of his own party to vote against the Treaty because of the changes the Senate added.

Before his defeat in the Senate, and against his doctor’s orders, Wilson embarked on an exhausting speaking trip to gain public support for his League of Nations.

Suffering from a massive stroke, Wilson spent the last year and a half of his second term secluded in the White House under the care of his second wife, Edith, who was his nurse until he died in 1924.

America would remain in isolation and elect the banal and corrupt Warren G. Harding, who promised a “return to normalcy.”

Europe’s return to “normalcy,” however, would be to allow the growth and spread of fascism in Germany, Italy, and Spain and British Prime Minister Chamberlain’s claim that by giving in to Hitler’s demands he (Chamberlain) had obtained “peace in our time.”